Kilian Jornet’s Gut Microbiome: a case study in how to not analyze/publish microbiome data

The paper

On Sept 17, 2024, the Journal of Athletic Training published “The Gut Microbiota characterization of a World-Class Mountain Trail runner during a complete competition season: a case report”, where Kilian Jornet’s gut microbiome was studied across the 2022 trail racing season.

While this paper is interesting, it is missing crucial data/parameters that should be reported and makes strong claims that either (A) the evidence does not support, or (B) methods do not support.

I don’t think that this paper should have passed peer review in its current state, and it is concerning that the Journal of Athletic Training allowed this to be published without addressing these issues.

These data are certainly interesting and worthwhile, but improper analysis and reporting are not acceptable and would have been caught by most researchers with microbiome expertise. An equal burden falls on the editor/reviewers in addition to the researchers.

My goal

I’ve attempted to summarize for a non-microbiome researcher (or beginner microbiome researcher) where this went wrong.

Issues with the paper

Summary

- The paper does not meet minimum information of reporting human microbiome data

- Diversity estimates cannot be compared between samples

- Diversity estimates cannot be compared to other studies

- Data are relative abundances, but not visualized as such

- Results are not provided with caveats

- Data and code are not available (analyses are not reproducible)

1. The paper does not meet minimum information of reporting human microbiome data

When you publish a microbiome paper, you need to report certain kinds of information. Some of these are basic, such as:

- “How were samples stored and transmitted to the lab?”

- Microbes continue to grow/die if not properly stored. Variation in time at room temperature could affect the data (source), but it was not mentioned.

- “Did the participants take antibiotics?”

- Antibiotics will wipe out a lot of microbes in the gut. This is very relevant information, but we don’t know if “the participant” had taken antibiotics throughout the year.

- “What was the timeline for sample collection?”

- This information is provided but not clear. There are 6 samples throughout the season, with 2 of those in pairs before/after races (Zegama & UTMB). However, there is no detail on how long before/after races samples were taken, nor is there information on when the other samples were taken relative to the other races, such as Sierre-Zinal and the Hardrock 100.

There are also more detailed criteria that need to be provided. Though I would expect non-microbiome researchers to request information for the previous questions, the questions require some expertise or previous knowledge. However, these are questions that any graduate student who has analyzed microbiome data would ask, such as:

- “How deeply were samples sequenced?”

- The researchers rely on sequencing a part of the bacterial genomes to know which bacteria are present. However, if they only sequenced that part of 10 genomes, we wouldn’t consider this an accurate representation of the microbiome. Maybe they sequenced many more than that, but we don’t know.

- “Were chloroplast and mitochondrial reads removed?”

- Chloroplasts (the green things in plants that make sugar from sunlight and carbon dioxide) and mitochondria (the powerhouse of the cell) also have this gene. The researchers don’t state if they considered chloroplast and mitochondrial reads in the analysis, which is important because the data on what bacteria make up the samples were presented as precents of the whole microbiome, so variation in chloroplast/mitochondria will affect the data.

- “What quality control steps were performed, and what were the parameters?”

- Parameters such as the minimum genome sequence length and quality should have been reported.

- “What was the rarefaction depth?”

- I’ll get into this in the next section…

Any reviewer who has analyzed microbiome data should have asked these questions. They are all part of the checklist for minimal information that is required at most journals regularly publishing microbiome research, based on the STORMS Checklist. The Journal of Athletic Training should require this information if they are going to publish a microbiome that is focused on the gut microbiome.

2. Diversity estimates cannot be compared between samples

The problem

Measures of microbiome diversity are sensitive to how deeply a sample is sequenced. To rephrase that, if we’re counting the number of species in a sample, that is dependent on how many genomes from that sample you assess.

An example

Here’s a toy example of where that would be an issue. The numbers are small and exaggerated for the example.

My microbiome has 100 species. The less-famous-than-Kilian-but-more-famous-than-me ultrarunner Jackson Brill has a microbiome with just 50 species.

If we only look at 10 random bacteria from my microbiome (sequencing depth=10) but 50 random bacteria from Jackson’s microbiome (sequencing depth=50), the we would likely see more species in Jackson’s microbiome than mine.

However, that’s because we looked at more individual bacteria. Had we looked at the same number of individual bacteria between our microbiomes, we would have likely seen that I have more species in my gut than Jackson.

When we sequence genomes for microbiome analysis, we can’t control how many individual sequences we get (i.e., how many individual bacteria we look at). To address this, it is common practice to either:

- Control for it statistically (doesn’t always address bias and couldn’t be done here because they didn’t do any statistical modeling, so I won’t get into this here)

- Throw out a random part of our data so that the samples look at a certain number of sequences (this is called rarefaction)

- In our example, we would only look at a random 10 bacteria from Jackson’s microbiome, so we could compare it to mine. We could even pick random combinations of 10 microbes from Jackson’s microbiome over and over to take some of the chance out of it.

Where the paper went wrong

This paper does not describe any steps taken to control for differences in sequencing depth (i.e., the number of individual bacteria considered for each sample). They discuss changes in microbiome diversity over the course of the season, but we have no idea if those changes were a result of differences in sequencing depth across the different samples.

Of course, the researchers might have rarefied their data to make it possible to compare samples, but they do not mention it once. If they did so, that needs to be reported both for clarity, reproducibility, and comparability to other studies.

3. Diversity estimates cannot be compared to other studies

Lack of rarefaction

The researchers compare the participant’s microbiome data to other athletes from other studies. This is an unfair comparison because the data were rarefied (or not rarefied) to different depths. In one of the studies that Kilian is compared to, the authors seem to mention a rarefaction depth of 10,000 reads per sample. The other paper by Grosicki et al. does not describe any rarefaction, so there is no basis that these data are comparable to each other.

Differences in sequencing methods

Additionally, the other studies use different genetic sequencing technology and protocols, which further make samples across studies not comparable.

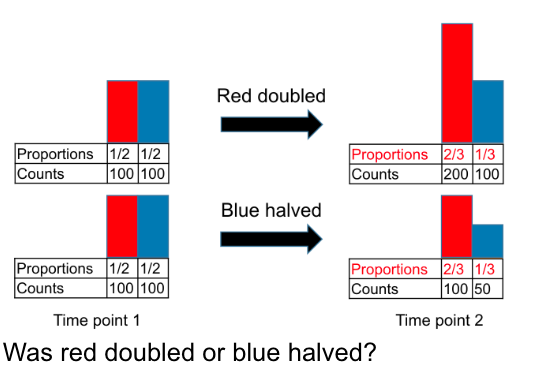

4. Data are relative abundances, but not visualized as such

Representation of compositionality in the paper

The authors mention percent relative abundance, but their visualization doesn’t represent this… I’m not sure if I can legally host a screenshot of the paper (per copyright law, especially since I’m not saying very nice things about the journal), but the bars in Figure 2 (in the paper, not shown here) should add up to the same height. This is also another component of the paper that makes me think that the data were not rarefied.

Saying that microbes increase or decrease after a race assumes that the total number of microbes in the microbiome is constant, based on the data at hand, but that assumption is not mentioned.

There is no mention of compositionality as a limitation in the paper.

Another complaint about figure 2

I don’t like to nitpick, but I think this matters. There’s no y-axis label on Figure 2 in the paper. The title says “GM Changes (%) Pre-Post Races”, but they are not showing change data (since there is a “pre” bar and a “post” bar), nor could they show percent change as a stacked barplot. There are no units, and the bars do not have the same height, which they should if the percents all add up to 100% (which all compositional samples should).

Additionally, multiple genera (a group of closely related species) are represented by the same color in the bar plot, so it’s difficult to tell what genera are changing.

5. Results are not provided with caveats

There are no limitations to the data described other than “This is only one athlete’s data”. The limitations section for even a well-designed study should be at least a paragraph long, given current methods in microbiome work. We’ve already discussed multiple limitations, such as the inability to compare to other studies and the relative abundances (compositionality).

There are other limitations, such as the fact that they don’t know how much day-to-day variation exists in Kilian’s microbiome, so claims that certain taxa increased/decreased are not relative to what a normal increase/decrease is.

Additionally, there are biological limitations to what they discuss in the discussion section. For example, there can be big differences in what microbes do in the gut, even within the same species. One strain of E. coli may be healthy in your gut, and the other could nearly kill you. The authors make a lot of claims about the biological functions of the microbes they identify, which are based on some other research, but not guaranteed or measured in these samples. Some speculation is okay, but some of the main sentences in the conclusion are about the function and pathogenicity of certain microbes, which I think takes it a bit too far. It isn’t entirely unreasonable for a case study though.

6. Data and code are not available (analyses are not reproducible)

I was talking about my qualms with this paper, and someone asked why I don’t just reanalyze their data in a way I think is correct. That is a fantastic question.

I would love to reanalyze these data. It is common practice to make data and code for your analysis publicly available. Nearly every journal requires statements about data availability.

However, the data are not available. Apparently, The Journal of Athletic Training does not require a data availability statement, since it’s nowhere to be found. Their analysis cannot be reproduced or altered.

A caveat - I understand that Kilian may not want his exact microbiome data to be public. That’s entirely reasonable, but there should be a statement regarding patient data confidentiality.

Summary

I appreciate the work of the authors to put together such a case study. It is lovely that Kilian has participated in provided this fantastic data, and I’m grateful for how transparent he’s been about his training and physiology. However, to quote the paper itself:

Prerequisites for the successful inclusion of [gut microbiome] analyses in training control are the use of appropriate methods of analyses and proficient interpretation of results.

Both the authors and the journal should be held to the minimum standard of reporting on microbiome research. These standards (such as the STORMS checklist) exist to increase the likelihood of proper methods, as well as the communication of caveats.

The lack of rigor in the microbiome analysis and reporting indicates a lack of thorough peer review regarding the microbiome. This may be because microbiome studies are outside the scope of the journal’s expertise. If that is the case, it is the responsibility of the journal’s editor to identify that, or to make sure the paper gets a thorough review from someone with microbiome expertise.